[ad_1]

Flashes of neon pink, acid yellow and lime green furniture shine from a first-floor terrace in Southwark, London, bringing a zinging taste of sunnier climes to a nondescript street of offices and apartments. They are the first signs that, after almost 10 years without a home since its Covent Garden base closed down, the Africa Centre is back – with a bang.

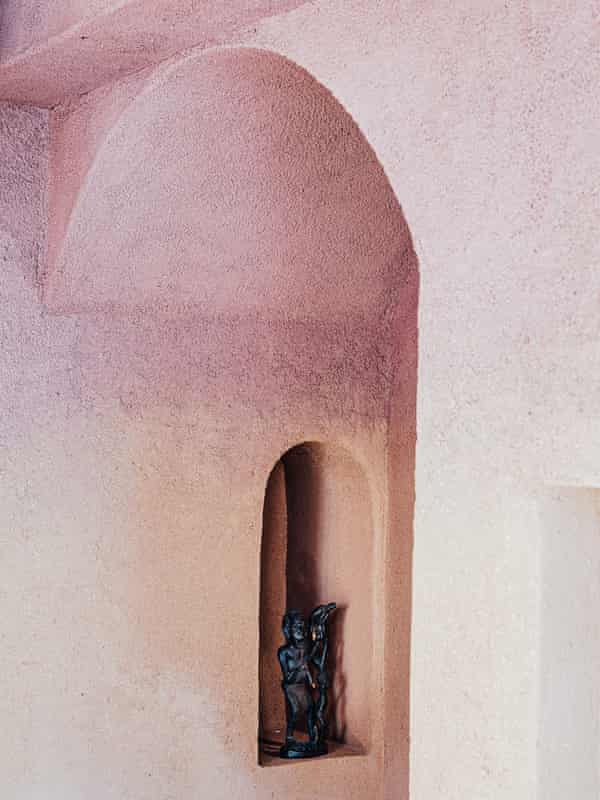

Step inside the black-painted brick building and you find an unexpectedly warm world of sandy clay plaster walls, carved timber furniture and woven light-fittings, where metallic beaded curtains and rows of arches frame dining platforms and cosy seating nooks. Alluring fabrics cover the cushions, while perforated blocks line the restaurant counter and seating booths, recalling the brise-soleil screens of modernist architecture on the African continent.

It is unrecognisable from the dingy 1960s office building that architects Freehaus and interior designer Tola Ojuolape were faced with when they began the project to create what has ambitions to be “the most welcoming cultural space in London”.

“We wanted it to feel inviting to the broadest possible audience,” says architect Jonathan Hagos, co-founder of Freehaus. “Not the kind of place where you have to make a commercial transaction to be there, but an open, welcoming, accessible space for anyone with an interest in Africa – whether they are African or not.”

The new centre has a tough act to follow. Originally founded in 1964 and opened by Kenneth Kaunda, then the newly elected leader of independent Zambia, the Africa Centre became a vital hub of political and cultural activity for the diaspora. Home to a lively bar, restaurant and music venue, it was a place where independence movements were fuelled and anti-apartheid struggles debated, and where the public statement from Nelson Mandela was famously released during his imprisonment on Robben Island. Archbishop Desmond Tutu would meet Thabo Mbeki here, while the resident Soul II Soul sound system presided over wild nights in the basement, and artists including Sonia Boyce and Lubaina Himid exhibited their mesmerising paintings upstairs.

In the 2000s, the centre fell on harder times and the leasehold of the Covent Garden building was sold in 2013, despite vocal opposition from the community. The proceeds of the sale, along with £1.6m from Arts Council England, were used to acquire the little office block in Southwark – in a prime location, just 10 minutes’ walk from Tate Modern. It was a smart move, using income generated from retaining the Covent Garden freehold to subsidise its activities, with an additional £1.6m from the mayor of London’s Good Growth fund for the capital project. In the hands of Freehaus, the building has been cleverly stripped back and carved open, with a series of low-cost interventions that utterly transform the space and make the tight construction budget of £2.6m go a long way.

The ground floor has been extended at the back, with a row of glass doors that fold open completely, connecting the restaurant to an animated alleyway of railway arches, lined with cafes, bars and a theatre, where the centre also has a pair of units housing startup office space. It makes a fitting venue for the first permanent home of Tatale, a former supper-club run by Akwasi Brenya-Mensa, who has conceived the new restaurant as a homage to the chop bars of Ghana – “a hub of conversation set literally around food”. Overlooked by a bar terrace, the stage is set for animated conversations to spill out into the alley, forming the soulful centre of what is hoped will become a new African Quarter.

Introducing a sense of openness to the uninviting office block was key, and the architects have punched a big new level access entrance into the front of the building, framed by a sturdy black steel canopy that supports the terrace above – “celebrating the users as part of the facade,” as Hagos puts it, in the manner of the nearby Young Vic theatre. A new staircase leads up to the first-floor bar, past a striking mural by the late Mozambican artist and poet Malangatana Ngwenya, which was painstakingly removed from the centre’s previous home, restored and reinstated here. It leaps out from a deep indigo-coloured wall, rendered in the same textured clay plaster, echoing the rich hues of traditional west African dyes.

“The brief was to be unmistakably African,” says Hagos, “but we wanted to avoid continent-sweeping generalisations and superficial stereotypes. My family is from Eritrea, which has an aesthetic that is very much informed by its Italian colonial past – completely different to a Nigerian or Ghanaian perspective. We didn’t want to bring too specific a viewpoint of what Africa looks like, but celebrate what we have in common, and show what an embassy for a continent might look like in the 21st century.”

Rather than resorting to well-trodden visual tropes, the designers came up with a series of common themes, including strongly expressed thresholds, tactile surfaces, quality of light, and reuse and appropriation. Look closely and you will notice that the earthy render on the ground floor intensifies in colour as it rises through the building, graduating from sandy shades, through pinkish tones, to a rich terracotta as it ascends the levels, its texture becoming more coarse as it climbs. Moments of transition are celebrated, such as in the polished green terrazzo, flecked with pink stones, that marks a step into the restaurant, as are hand-crafted elements such as the chunky fitted furniture, made by Kenyan and UK-based designers Studio Propolis.

Even some of the ragged scars have been preserved from where the building was sliced open, leaving gnarled areas of chipped concrete and exposed steel reinforcement above expanses of new thermally efficient glazing. “We wanted to acknowledge that by retrofitting this quite drab 1960s building, the Africa Centre is making a big gesture already,” says Hagos. “We’ve tried to include as many passive environmental measures as possible, like using the staircase as a thermal chimney for natural ventilation, but keeping the building” – and avoiding the carbon-hungry act of demolition – “is something they should be really proud of.”

A second artwork-lined staircase leads to the third-floor gallery, one of the most evocative spaces in the building, drenched in the same inky indigo blue as both stairways, at Ojuolape’s instruction. Faced with a lack of wall space, the architects took inspiration from Sir John Soane’s Museum and have designed a clever system of panels that fold out from the walls to provide more hanging surface, creating booth-like nooks for the artwork.

The intense colour choice might sound overwhelming, but it provides the perfect backdrop for the opening exhibition of dazzling paintings by Tanzanian artist Sungi Mlengeya, whose balletic black figures shine out from their bright white canvases, powerfully occupying the space with their joyfully liberated limbs (and perhaps foreshadowing some of the shapes that might be thrown in the bar downstairs).

A second phase of work, currently seeking funding, will see the third and fourth floors transformed into an educational space, to be digitally connected with classrooms in Africa, and an incubator for Afrocentric businesses, along with plans for a mashrabiya-inspired screen to cover the facade of the building. Designs for illuminated rooftop lettering, facing the railway to announce the centre’s presence, were sadly vetoed by local planners, but all signs suggest that the energy emerging from this self-styled “embassy of optimism” will reverberate far and wide, regardless.

[ad_2]

Source link