[ad_1]

For anyone thinking of building a low-carbon office, there is a dilemma to resolve. Timber is a good choice for a structural frame due to its lower embodied carbon; better than steel or concrete. But wood is not as strong as traditional materials, so the structural members need to be bigger, eating into valuable lettable space.

This is particularly undesirable in high-value areas like central London. And there are negative perceptions about fire performance, although this is less problematic than for residential buildings as different rules apply. These issues have not deterred co-working and flexible office space specialist The Office Group from going for a timber-framed office for its first new-build project, however.

The new building replaces a former four-storey Office Group co-working space called the Black & White Building on Rivington Street, a narrow road fringed by former warehouses, restaurants and bars in the heart of Shoreditch. The £19.3m project, which bears the same name, makes the most of a constrained plot which is hemmed in on three sides by adjacent buildings to the west and rear and a railway line separated by a yard to the east.

The new building is a game of two halves. Its front half features a cutaway to get light into the lower floors on the west side and is five storeys high in order to avoid towering above its neighbours, while the six-storey rear section fills the width of the plot. A single-storey basement has been added to create more space.

The architect, Waugh Thistleton, is one of the UK’s foremost timber-frame specialists and was responsible for the world’s largest cross-laminted timber (CLT) residential building, the 10-storey Dalston Works located in nearby Hackney. The new Black & White Building will be London’s tallest timber office building when it completes next year.

Client and architect wanted to reduce embodied carbon as much as possible, so the building features a CLT rather than concrete core and has timber-framed curtain walling and wooden brise soleil. According to Waugh Thistleton, if this office building was built from concrete the embodied carbon impact would be 622kg CO2e/m2.

The low carbon features of this building crunch the embodied carbon impact down to a commendable 256kg CO2e/m2 if the carbon sequestrated in the timber is included, which betters LETI’s embodied carbon target for buildings built after 2030. If sequestration is discounted, the impact is 477kg CO2e/m2 which is still better than concrete.

Crucially, this building employs a little-used engineered timber product called BauBuche that goes a long way towards addressing the structural space issue, although the material has its own peculiar construction challenges.

BauBuche is a hardwood laminated veneer lumber, an engineered product made from very thin layers of beech, giving it the appearance of oversized marine plywood.

It has been used for the beams and columns of the Black & White Building, and the difference between it and the more commonly used alternative, glulam, is obvious. BauBuche is darker and warmer than glulam and, as a hardwood made up of thin layers rather than large blocks, it has a sharper, crisper appearance. In short, it is the difference between an Ikea pine desk and a hardwood one from Heal’s.

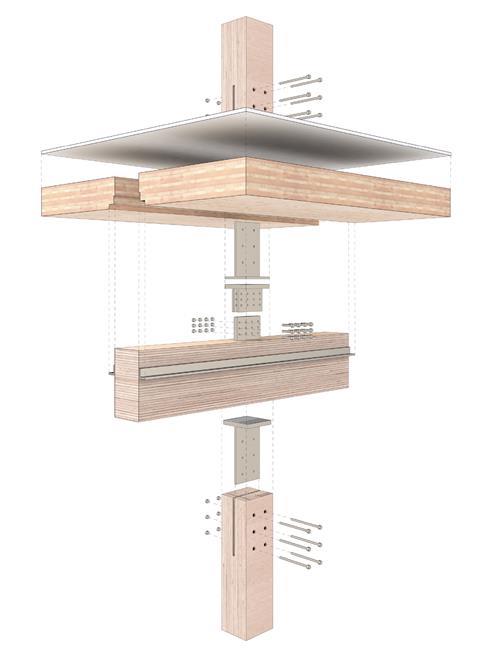

The main reason BauBuche has been used is for its structural benefits. According to Toby Ronalds, a director at structural engineer Eckersley O’Callaghan, BauBuche is 2.9 times stronger than glulam in compression and bending because beech is denser and stronger and arranging it in thin layers creates a stronger product than the short blocks used in CLT and glulam.

The columns are 350mm square in the Black & White Building, compared with 450mm if it were glulam, and the beams are 650mm deep rather than 850mm for a glulam equivalent. The beams are critical in offices because of the space needed for service runs.

“A lot of the standard open-plan timber structures have big downstand beams, and the real challenge is what that does to your floor-to-floor heights and how you co-ordinate the services with those beams,” Ronalds says. “There are various approaches to that and here the approach was to minimise the depth of the beam.”

The beams are partly buried in the CLT floor slabs, which are 220mm thick with up to 80mm of the beam projecting above the slab as this is covered up by the raised access floor. This means that just 350mm of the beam projects below the slab, as opposed to 550mm for glulam. Crucially for an office, and unlike glulam, BauBuche can have notches cut into it for service runs, further reducing the space needed for services.

The frame went up in 16 weeks with six men, and you don’t have a concrete gang or steel fixers. We’ve had so many compliments from local businesses about the lack of noise

Graham Turner, project leader, Mid Group

Dave Lomax, senior associate at Waugh Thistleton, says the difference between glulam and BauBuche could add up to an extra floor. “If you end up with a building that is half a storey too high, then you have lost the whole of that storey as you can’t build half a storey,” he says. “So those small gains in height do make a big difference.”

Visually, given the scale of the building, the frame looks very minimal for a timber frame and is in keeping in scale with steel. This is confirmed by Ronalds: “The columns are weaker than steel but the whole building is lighter than a steel frame with concrete floors, so you are getting a timber frame that is pretty close to the scale of a steel frame,” he says.

Graham Turner, project leader for contractor Mid Group, which is delivering the building under a design and build contract, is full of praise for timber-frame construction. “The difference between a steel or concrete frame is phenomenal,” he says.

“The frame went up in 16 weeks with six to eight men, and you don’t have a concrete gang or steel fixers. We’ve had so many compliments from local businesses about the lack of noise.”

The frame construction needed careful planning because BauBuche is so hard it cannot be easily cut on site. “It needs to be pre-cut, so you need a lot of early involvement from the M&E consultant,” says Turner. The frame was built by Hybrid Structures, part of the William Hare Group, which is principally known for steel fabrication and erection.

Between two and three lorry-loads of timber arrived each week, with the frame and slabs loaded onto the lorry in the right sequence for erection. The lorry was parked up in the loading bay for the day while the frame fixers erected the frame. Edge protection was fitted to the CLT slabs at ground level to eliminate the risk of doing so at height.

The frame has been designed to be fully demountable so it can potentially be reused – for example, the wooden plugs covering the bolts attaching the LVL (laminated veneer lumber) members to the steel connection plates are clearly visible, making it easy to identify where the bolts are located to dismantle the frame.

Hardwood LVL does have one disadvantage compared with CLT and glulam: it doesn’t like water. “The biggest challenge is rain,” says Turner. “We started [the frame] in May, which was the fourth wettest May on record.”

BauBuche comes with a protective coating which the team thought would be sufficient to stop water damage during construction, and CLT is reasonably forgiving of rain during construction, particularly as it comes with a protective plastic layer stuck to the boards. The end grain of BauBuche is particularly vulnerable as it is composed of many thin layers, unlike CLT and glulam which are made from much thicker blocks.

Water can get between the layers, causing the affected area to swell up, which unfortunately happened at the Black & White Building. “Everyone is used to working with CLT and, as no one had worked with Baubuche before, we didn’t know it was going to happen,” says Turner.

He quickly came up with a water management plan to ensure there was no further water damage. This included putting plastic bags over the exposed ends of the columns as the frame went up and ensuring that water could be cleared from the CLT slabs – each one acts as the building roof until the next floor is erected.

This involved fitting the upstand beam that sits on the CLT slab around the building perimeter after the floor above had been added so water could drain or be swept off the edges. Temporary outlets have been created on the roof to allow the water to drain.

Additional protection was provided over the top of the LVL beams by extending the plastic sheet attached to the CLT over the beam and taping it down. The damaged column was repaired by the simple expedient of cutting away the swollen sides and splicing in a new piece of LVL so the repair is almost invisible.

With the frame completed, work is now progressing on the cladding and interior works, including the services installation and raised access floors. Scaffolding fitted with Monaflex sheeting keeps the weather out until the facade is completed. The scaffolding features telescopic poles so it can be retracted back from the frame construction to allow the facade to be fixed.

Turner says the lift supplier, Ideal Lifts, was delighted with the accuracy of the CLT lift shaft as concrete shafts need more adjustment of the lift frame to bring these within tolerance.

The glulam frame for the curtain wall is in place and the glazing is now going in. The glulam will feature an aluminum capping to protect it from the weather. Solar gain is being controlled using vertical tulipwood louvres on the north and west sides and horizontal louvres on the south elevation. The east side features rainscreen cladding.

According to Lomax, tulipwood has several advantages: it is a soft hardwood, making it easy to work, and is in oversupply in North America which means it ends up chipped for biofuel. “It is a really interesting opportunity to use something that is in need of a use,” says Lomax.

Sunlight paths across the building were modelled so the louvres get progressively deeper towards the top of the facade to maximise the amount of daylight getting into the building while controlling solar gain.

Hardwood LVL is more expensive than glulam or CLT, but Ronalds says the amount of material in the columns and beams is tiny compared with that in the floor slabs, making the premium relatively small. And central London’s high rents mean that the extra space gained from using hardwood LVL makes it a price worth paying.

In terms of insurance, Lomax describes the insurance market over the past 10 years as “a challenging environment”. He says: “We have shown lots of insurers and underwriters around this building, and what we are hearing is those markets understand that this [zero carbon] is on the way, and by far the best thing for them to do would be to understand and support it better. I think that market is changing and becoming more supportive.”

This proves that you can do a building like this right in the middle of messy, dirty, difficult Shoreditch – and that it will look like what people said it would look like

Dave Lomax, Waugh Thistleton

How tall could a hardwood LVL framed office be? Ronalds says that the Black & White Building is at the limit of how high an all-timber building could go – any higher would necessitate a concrete core.

A big cross brace has been incorporated towards the back of the front, five-storey section to add stability because the core is located in the centre of the six-storey element. In terms of how high a concrete-cored, timber-framed office could go, Ronalds says it gets to the point, around 15 to 20 storeys, where it makes sense to switch to a steel frame.

He adds that 70% of the embodied carbon at the Black & White Building is in the basement and foundations because these are all concrete. “We are all pushing the net zero approach above ground but are leaving behind what is below ground because at the minute we don’t have a solution,” he says. “Maybe there could be a planning rule where you could have another floor on top and not dig the basement.”

For Lomax, who is at the leading edge of timber-framed construction development, the Black & White Building has been a positive experience. “This proves that you can do a building like this right in the middle of messy, dirty, difficult Shoreditch – that it can be funded, warranted and insured, it can be delivered, that it will look like what people said it would look like.

“There isn’t a compromise – we have done so many timber buildings that have quite a lot of steel because that was the way to make it work. There aren’t many buildings that do that at this kind of scale in central London.” Which means we are now sure to see more all-timber offices like this one in the future.

Project team

Client The Office Group

Architect Waugh Thistleton

Structural and facade engineer Eckersley O’Callaghan

M&E engineer EEP

Cost consultant Gardiner & Theobald

Project manager Opera

Contractor Mid Group

Structural frame specialist Hybrid Structures

[ad_2]

Source link