[ad_1]

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/W6JCNJBJYFFFLBPAC2GDGEQPRY.jpg)

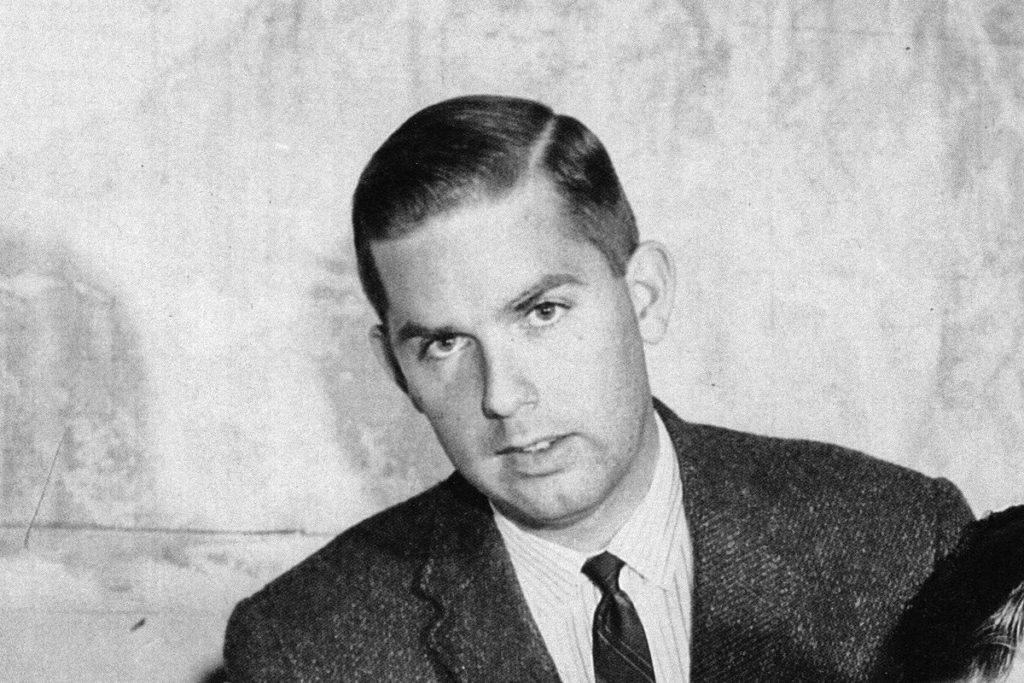

British Columbia architect Barry Downs, left, with fellow architect Richard Archambault.Handout

In the postwar Mad Men era, when the ruthless alpha-male professional reigned supreme, Vancouver architect Barry Downs presented an anomaly. Soft-spoken, modest, and devoted to both architecture and family life, he brought a rare sensibility to 20th-century Canadian architecture. His death on July 20 at age 92 marked the passing of one of the last giants of the cohort known as the West Coast Modernists.

Mr. Downs built his career in the second wave of postwar modernist architecture, when verdant lots on the West Coast were cheap and plentiful. The timing allowed him to benefit from the mentorship of the earlier architectural trailblazers, including Ned Pratt and Ron Thom.

As he built his career through the late 1950s and 1960s, his work bridged the often-austere high modernism of the day with a more earthy, organic sensibility that fit the coastal context. In addition to award-winning homes in the Vancouver area, he made his mark designing high-profile buildings that included the North Vancouver Civic Centre, Britannia Community Services Centre, Lester B. Pearson College of the Pacific (with Ron Thom as lead designer), and the Frederic Wood Theatre at the University of British Columbia.

Barry Vance Downs was born in Vancouver on June 19, 1930, to a typewriter sales executive and a homemaker. His appreciation of architecture began around age five, when his parents enlisted architect C.B.K. Van Norman to design their family home in Vancouver’s West Point Grey neighbourhood. The home’s steeply pitched roof, timber and stucco gables, baronial oak-plank front door, and huge garden enthralled the young boy.

He attended Lord Byng High School, where developed an interest in drawing and woodworking. During this time, he forged a lifelong friendship with Art Phillips, who later became one of his first clients and later still one of the most transformational mayors of Vancouver.

After graduating from Lord Byng, he ceded to parental pressure to study commerce at the University of British Columbia. Bored and restless after two years, he left UBC and moved to Seattle to study architecture. Although the local university had just established its own architecture school that very year, Mr. Downs was more keen on the University of Washington’s well-established programme.

When he returned to his hometown in 1954, he apprenticed at the city’s most prominent firm, Thompson, Berwick, Pratt & Partners; he later called the firm “my much-appreciated ‘graduate school.’” There, he enriched his education through real-world project experience and mentorships. “The major turning point for me was the introduction to Ron Thom and Freddy Hollingsworth and Doug Shadbolt – that whole gang,” Mr. Downs recalled in a 2012 interview with this reporter. “All my work at the University of Washington was directed toward Mies van der Rohe’s idea of minimalism. But I discovered a whole other design approach here, and I’m forever grateful for that.”

From those early mentors and peers, Mr. Downs absorbed not only their famed sensitivity to the West Coast landscape, but the emotional and sensory aspects of design. “At the start, I didn’t realize that architecture isn’t all about construction and engineering and huge glass walls open to the views. It also has much to do with exhilaration in being in certain spaces,” Mr. Downs said. He began to question his earlier allegiance to the Miesian mantra of austerity, openness and precision – which, he came to realize, did not suit every need in every region. While he continued to appreciate the aesthetics of minimalism and the excitement of new materials, he recognized the human need for organic texture and form – especially on the West Coast.

In 1955, Mr. Downs wed Mary Stewart, whom he had met several years earlier on nearby Bowen Island. The following year, he and Mary spent several months on an international pilgrimage to major architectural landmarks. After touring Frank Lloyd Wright’s houses in Oak Park and Wright’s Johnson Wax Building in Wisconsin, they viewed the new International Style towers in New York. From there, they sailed to Europe, where Mr. Downs toured Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation apartment building in Marseilles and other examples of then-radical architecture, before returning home to start a family and design their own home.

In 1957, the couple welcomed their first child, Bill; a second child, Elizabeth, arrived three years later. “Dad was a craftsman at every level, always building things,” his son says. The younger Mr. Downs, an avid guitarist, recalls that at age five, his father made him his first instrument by cobbling together a cigar box, a one-by-two piece of wood, and some fishing line.

Mr. Downs’s love of craft, landscape, drawing, and watercolours helped endear him to the star designer at Thompson Berwick Pratt, Ron Thom, who enlisted him to render the hand-coloured presentation boards for the 1960 Massey College competition as well as hundreds of his other projects.

Meanwhile, his role was transitioning from an illustrator of others’ work to a full-fledged designer in his own right. His breakout designs include the 1957 house for his friend Art Phillips; the 1958 Ladner Pioneer Library, designed in collaboration with TBP colleagues Richard Archambault and Blair MacDonald; his own 1959 family home, a glass-and-brick bungalow with an artfully jogged façade; and the 1963 Rayer Residence.

Despite the punishing hours required at TBP, Mr. Downs made every effort to devote time and support to his growing family. His soft-spoken ways did not always serve him well in a workplace full of swagger and braggadocio. He toiled diligently and patiently at TBP, winning acclaim from others and expecting to become a partner in due course. But in 1963, his boss, Roy Jessiman, told him that they were focusing on bringing more young blood into the firm and that, although just 33, Mr. Downs was already too old to be considered for a future partnership.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/FPPEYY5D65CNROBEE62Z7YU4LQ.jpg)

Barry Downs made his mark designing buildings like the Frederic Wood Theatre at the University of British Columbia.Selwyn Pullan/Courtesy of the West Vancouver Art Museum

He then left Thompson Berwick Pratt to start a firm with Fred Hollingsworth, though their skill sets weren’t entirely complementary. Both were accustomed to taking a strong lead in the design, and Mr. Hollingsworth’s penchant for Frank Lloyd Wright was different from Mr. Downs’s more subdued and minimalist approach. What’s more, Mr. Downs hankered to design larger projects and public buildings, while Mr. Hollingsworth remained content to focus his artistry on single-family homes.

Mr. Downs left that partnership four years later to work independently but soon found himself overwhelmed by the demands of a one-person firm. His working hours grew even more onerous. As his son recalls, “I remember getting ready to go to school in the morning and he would still be up all night working on a project.”

In 1969, his life and career improved when he teamed up with architect Richard Archambault. Downs/Archambault proved to be a highly symbiotic partnership, as Mr. Downs now could focus more on design and Mr. Archambault served as a brilliant project architect and manager. While at Downs/Archambault, Mr. Downs designed or codesigned several important landmarks, including the North Vancouver Civic Centre, the Britannia Community Centre in East Vancouver, and Pearson College.

Throughout it all, he maintained his prowess as a house architect. One of his most important legacies still stands at the edge of the UBC endowment lands: the Oberlander House II, which was completed in 1972. Designed in close collaboration with Peter Oberlander, a prominent urban planner, and with landscape architecture by Cornelia Oberlander, the house was recently sold to a sympathetic buyer who plans to restore it.

In the late 1970s, he and Mary moved to West Vancouver and built their distinctive second family home, Downs House II, whose walls curve in a continuous plane into the roofline like an Airstream trailer. The house is the subject of an eponymous 2016 monograph by UBC architecture professor Christopher Macdonald.

The due recognition that had earlier eluded him came forth in the new millennium. The West Vancouver Museum hosted a solo retrospective of his work in 2013 and, earlier this year, launched an annual lecture named in his honour. In 2014, he was named to the Order of Canada.

Mr. Downs spent much of his later career collaborating with other architects on urban projects, including Vancouver’s Library Square by Moshe Safdie, and the Roundhouse Community Centre plan.

“Perhaps most extraordinary in Barry Downs’s career was his demonstrated ability to transform his practice from a modest, largely residential focus to expansive urban design projects,” Prof. Macdonald says. “It was precisely this ability that has given us an enduring sense of locale both in individual residential design and the distinctive contours of our cities.”

Barry Downs leaves his son, Bill Downs; daughter, Elizabeth Hewer; grandchildren, Susan and Curtis; and great-grandson, Jack.

[ad_2]

Source link